FEMINIST LITERARY CRITICISM’S OBJECTS OF STUDY

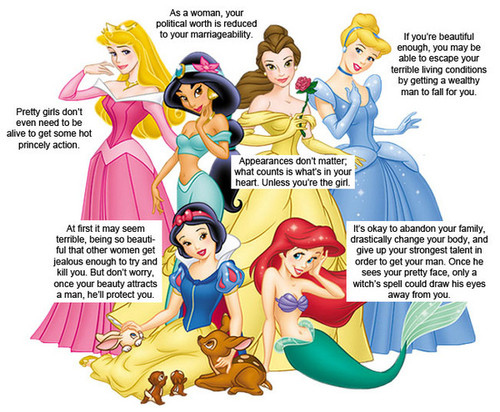

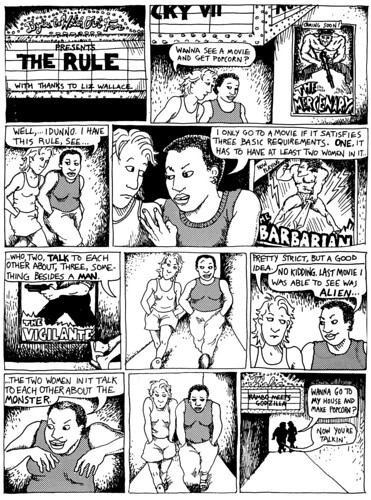

On the one hand, feminist literary scholars look at literary texts, and on the other hand, they don’t actually limit their objects to books, not even to what most people think of when we say texts. Films, games, and other objects can be examined using feminist critical theory and are sometimes incorporated under the umbrella of feminist literary criticism. For me, poetry is my object, but in what form that object is available is of little consequence. Poetry can be found in books, online, in film, as well as in places that are as yet undiscovered. I could imagine, as a scholar, analyzing not only the canonical and new poetry produced by literary poets but also the rhymes that appear in greeting cards, between lovers, and found incidentally in the world at large (By these “incidental” poems, I’m referring to those instances of “I’m a poet and didn’t know it” and poetic language that are recognized within our everyday discourse).

From by “Cultural Studies Examines the World with a Critical Eye” by Tara Laskowksi, George Mason University

The lines between literary scholarship and cultural studies often become blurred as feminist literary scholars expand out from the literary text. Both disciplines incorporate a variety of theoretical practices, so in essence they operate in similar ways. There are differences. Cultural studies approaches its objects of study in terms of production and distribution and “will consider the social, cultural, political and economic aspects of the distribution of power” (Ouellette) while feminist critical theory, the basis for feminist literary theory, focuses on the structures of power, entrenched patriarchal structures with respect to the Other.

Although many women and Others have found their ways into the literary canon, for me, my objects of study are too new for have found their places there. I intend to examine the poetry women are writing now, poetry that is newly published by women new to the field. I want to see how women are defining themselves and other women in their writing as compared to how women have historically defined themselves and others in poetry, perhaps even compared to how men have defined women through poetry.

WHY WE ANALYZE THEM

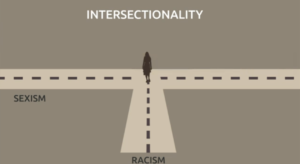

Feminist literary scholars analyze the ways the language of texts oppresses the Other. Feminist originally referred to women, specifically white middle class women, but that definition has broadened. Feminist literary scholars apply the various theoretical lenses that make up feminist literary theory to examine the power imbalances, which often result in oppression, that exist based on sex, race, class, and identity. Among the most recent concerns for feminist scholars is intersectional feminist studies in which the Other is multiply oppressed as their identity falls into more than one category of oppressed Other. According to Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality results in scholars following paths of inquiry only examining one type of oppression but missing that other types of oppression cross that path.

In my scholarship, I plan to look at a cross section of women so that I have a broad view of women from different and varied backgrounds; however, I suspect I will focus primarily on women who have had college level creative writing instruction. Still, I’m interested in seeing how their experiences shape how they create themselves in their poetry.

FINDING THE ANSWERS TO MAJOR QUESTIONS

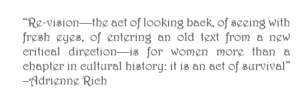

The major questions that scholars are addressing now are still related to the inclusion of women’s literature in the male canon, how women are portrayed through the phallocentric lens, and how they portray themselves in what is recognized as a male model of authorship (Wolosky 1), but feminist literary scholars have expanded out from middle-class white women as Other and out from literature in book as form. Without ignoring those, feminist literary scholars have expanded definitions of Other to include all people who fit into the category of Other; however, they have remained primarily centered on women and included other text forms.

THE STRUGGLE FOR ACCEPTANCE

Image Credit: Tingo’s Vocabulary System

Early feminist scholars faced considerable push back from the patriarchal bastions of literary studies. Male scholars held staunchly to their privileged literary canon; however, women within English departments made their cases for the inclusion of newly “discovered” women writers. Some male professors still argue the merits of learning the classics and the inability to make space for new works by women, but that position is becoming rarer as women’s and feminist studies have impacted how colleges and universities view their commitments to their students in terms of inclusion (Wolosky 1; Rich 349).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-nmxnmt_XU

Works Cited:

“Kimberlé Crenshaw: The Urgency of Intersectionality.” TEDWomen 2016 from TedTalks. Oct. 2016, https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality#t-612389. Accessed 17 Nov. 2016.

Ouellette, Marc. “Re: CS Project.” Received by Lori Hartness, 14 Nov. 2016.

Rich, Adrienne. “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-vision.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 345-61.

Wolosky, Shira. “Modest Muses: Feminist Literary Criticism.” Feminist Theory Across Disciplines: Feminist Community and American Women’s Poetry. New York; Taylor & Francis; Routledge, 2013, pp 1-22. Adobe Digital Editions. Accessed 26 Sept. 2016.