I became interested in women’s voices in poetry during my MA in Creative Writing and in attending the Juniper Writing Workshop at UMASS where, I discovered a community of poets, many women, who were newer poets,

My experience with the ways other scholars have approached literary criticism and my creative writing background have allowed me to approach literature under the lens of creative writing theory, which allows a critical approach based on the writer’s act of constructing the work to elicit specific responses from readers as well as the reader’s actual response, in Frost’s words, “No tears for the writer, no tears for the reader” (11), or Tess Gallagher, “the reader is also the maker of the poem as it lives again in his consciousness” (107).

Since I’ll be location bound once I’ve completed my degree, I have an eye to where the greatest need will likely be when I’ve completed the program. I will undertake my scholarship within the larger concentration of 20th and 21st Century American Literature because I do have to be employable after all. In all honesty, I could live in and love any era of literature, and in a sense, all the areas are interconnected. The broader lens, under which this women’s poetry falls, is American literature, I will continue my inquiry, collecting and comparing both poetry and fiction, because “No poet, no artist of any art, has is complete meaning alone….you must set him, for contrast and comparison among the dead” (Eliot 112). I will focus most heavily in the 20th and 21st centuries, to comparative work, I will need to expand out.

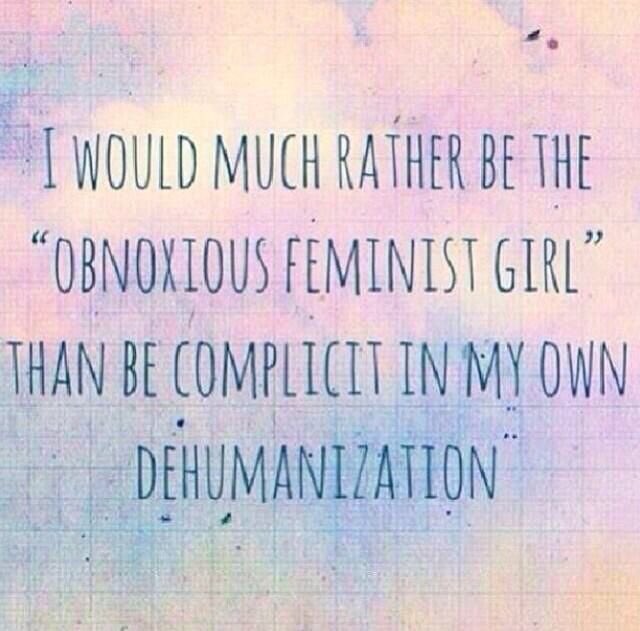

I need to define myself in terms of how my “own lived experiences reflect [my] literary commitments and affinities” and consider what other feminisms “look like” (Reed). Ihab Hassan quotes Steven Best and Douglas Kellner’s The Postmodern Turn, “Yet we must all heed politics because it structures our theoretical consents, literary evasions, critical rescuancies” (125). In these ways, scholars, including me, can avoid the unfortunate “you can’t speak for me”—“what about us” rhetoric and the vulnerabilities of early feminism and gynocritics that excluded and erased large populations of marginalized women.

Although I won’t eschew traditional theoretical paradigms, I intend for my professional alignment to be new, to deviate from what others have done, but not too far afield. As I remain open-minded, see what the theorists have told us, I can create new approaches. I had done so in my master’s degree work with much satisfaction and success. As feminist critical scholar, I will look at a cross section of women so that I have a broad view of women from different and varied backgrounds: women who have had college level creative writing instruction and those who have not. In adding to the scholarship on women writers, I will explore what women are writing about today and how their contribution to poetry has evolved since the beginning of the twentieth century.

My primary objects of study for my dissertation will be poems written by women to see how women are defined within that poetry because “[p]oetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought” (Lorde 283). I’m still open to new positioning and possibilities. Focusing on 20th and 21st Century, I will consider women’s poetry in linguistic terms, considering the works of Saussure, Lacan, and Freud to discover how poets establish feminine ethos. The authoritative works, the works that appear significantly in present critical theory, go back to the original feminist theorists: Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, Kate Millet, Elaine Showalter, and Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar and to gender theorist Judith Butler figure heavily in contemporary scholarly criticism.

My work will build on the multidisciplinary, encompassing “a revisionist engagement with history and literary history, a revision of aesthetic standards and a radical critique of the representation of gender and gender roles as a part of a larger critique of cultural self-definition” (Knellwolf 197). Theoretical approaches I will find most useful in interrogating texts include feminist, gender, creative writing, poetic, literary, rhetoric, cultural, Marxist, and linguistic theories. I see myself using many different theories and in combinations. My experience has been that the primary theories used are determined by the immediate task at hand. Since I want to explore how women define themselves and other women as women in poetry, questions of self-identification, language usage, creative expression, cultural positioning, and power and class structures all seem to be fruitful avenues of exploration. As T. S. Eliot says, “we might remind ourselves that criticism is an inevitable as breathing” (111).

Early Feminist Theory that relied on Freud and Lacan, Byam points out, is based on psychoanalytic approaches that are inherently misogynistic, implying that women desire to be men; however, blending the theories with new insights could produce exciting scholarship. Even the feminist’s initial dichotomy of gender becomes problematic (102). While discussing feminist approaches to earlier eras, Byam states that feminist criticism has never been formalist, “if formalism means being preoccupied or even more than superficially interested in technique” (108). As for method, the tried and true research, collecting and examining secondary sources and Close Reading of the material, is still widely practiced, but even that seems to be giving way to experiment as scholars explore philosophical theories like Derrida‘s Deconstruction, and his assertion, “Everything is a text” (Rawlings).

I will focus on the omissions, or erasures, of women from the history of literature, per Annette Kolodny, quoting Clifford Gertz, which “came to be ‘viewed collectively as a structural inconsistency’ within the very disciplines we studied” (1). So, my task will be to examine the poetry of people who identify as female. The question of what constitutes a woman and how that determination is made is key to my research because how can I examine women’s poetry without exploring that dilemma. Of course, “the way we view our bodies is synonymous with how we view ourselves” (Bleier qtd. in Grace 12), so with Judith Butler’s lead, considering gender as a construct and a performance and how women construct themselves female, the differences between women’s early writing and their mature writing should reveal whether their construction or (re)construction of gender over time reinforces or dismantles their earlier perceptions of their respective gender identities.

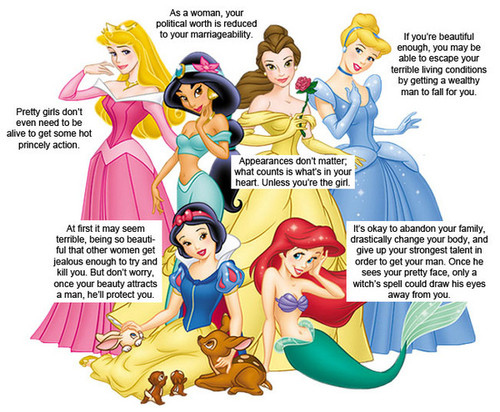

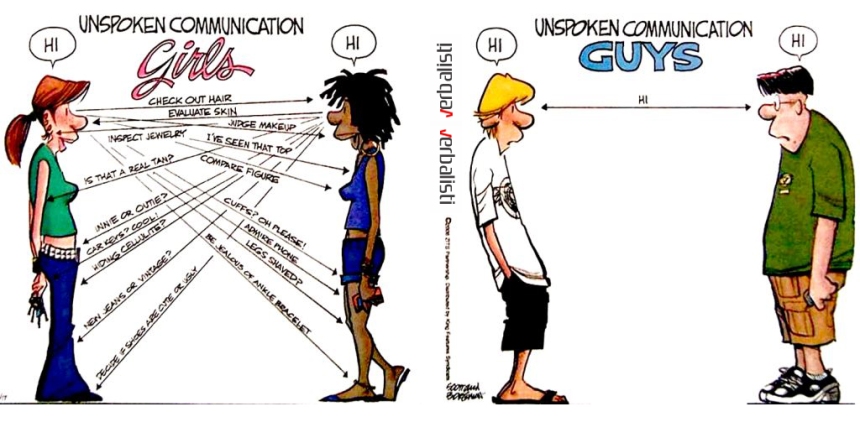

Lakoff’s “overall effect of ‘women’s language’…is this: it submerges a woman’s personal identity” (42), and as she continues discussing the differences in production and cultural expectation Men are still more recognized and more compensated for their poetic work, but she says, women are writing poetry, studying literature, and “looking eagerly for guides, maps, possibilities; and over and over in the ‘words’ masculine persuasive force’ of literature she comes up against something that negates everything she is about; she meets the image of Woman in books written by men” (351).

The major questions that scholars are addressing now are still related to the inclusion of women’s literature in the male canon, how women are portrayed through the phallocentric lens, and how they portray themselves in what is recognized as a male model of authorship (Wolosky 1), but feminist literary scholars have expanded out from middle-class white women as Other and out from literature in book as form. Without ignoring those, feminist literary scholars have expanded definitions of Other to include all people who fit into the category of Other; however, they have remained primarily centered on women and included other text forms.

Early feminist scholars faced considerable push back from the patriarchal bastions of literary studies, male scholars held staunchly to their privileged literary canon; however, women within English departments made their cases for the inclusion of newly “discovered” women writers. (Wolosky 1). Plain and Sellers say feminist literary criticism was the “culmination of centuries of women’s writing,” and of men “writing about women’s minds, bodies, art, and ideas” (2).

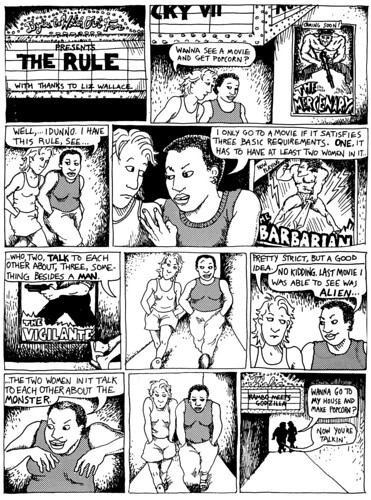

I will explore new paradigms to assess how women are portrayed in film, and in literature include approaches like Shira Wolosky’s, examining literature in terms of gender and cultural theories through a decidedly feminist lens, and Wolosky, and Cheryl Glenn’s, examining women’s silences and modesties as deliberate and political. And, Daphne M. Grace explores the female body in literature, “locating and discussing the relationship of the gendered body and consciousness” in writing by men and women (15).

I’ve never understood thinking out of the box. I plan to situate myself firmly in the box, surrounded by all that’s English and all that’s poetry. I want to examine and reexamine what’s already in the English box, keeping in mind that all that’s English belongs in the box. I plan to raid other boxes, those of the social sciences like history, sociology, psychology, and philosophy, and even perhaps, the hard sciences like computer science and mathematics. But my plan is to bring everything back to my hoard in the English box. I see the box as an English science lab and myself as the mad scientist, applying whatever I find that can be applied to the poetry I intend to examine. I also plan to pitch outdated and outmoded ideas from the box like the phallocentric view of literary studies that has enveloped the field of English for centuries and draw in the discoveries from women’s studies. I know this is no mean feat.

Works Cited

Byam, Nina. “The Agony of Feminism: Why Feminist Theory Is Necessary After All.” The Emperor Redressed: Critiquing Critical Theory, edited by Dwight Eddins. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 1995, pp. 101-17.

Eliot, T. S. “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Twentieth-Century American Poetics: Poets on the Art of Poetry, ed. Dana Gioia, David Mason, and Meg Schoerke. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2004, pp. 111-16.

Frost, Robert. “The Figure a Poem Makes.” Twentieth-Century American Poetics: Poets on the Art of Poetry, ed. Dana Gioia, David Mason, and Meg Schoerke. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2004, pp. 11-12.

Gallagher, Tess. “The Poem as a Time Machine.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 104-116.

Grace, Daphne. “Cognition, Consciousness, and Literary Texts.” Beyond Bodies: Gender, Literature, and the Enigma of Consciousness. New York; Rodopi, 2014, pp 9-32. Adobe Digital Editions. Accessed 26 Sept. 2016.

Hassan, Ihab. “Confessions of a Reluctant Critic: or, The Resistance to Literature.” The Emperor Redressed: Critiquing Critical Theory, edited by Dwight Eddins. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 1995, pp. 118-31.

Knellwolf, Christa. “The History of Feminist Criticism.” Twentieth-Century Historical, Philosophical and Psychological Perspectivesedited by Christa Knellwolf and Christopher Norris. The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism Vol. 9. Cambridge UP, 2007, pp. 193-205. Cambridge Histories Online. https://www-cambridge-org.proxy.lib.odu.edu/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/D5A1D2AF4184FBC9438F19EF62A01E09/9781139055376c15_p191-206_CBO.pdf/the-history-of-feminist-criticism.pdf. Accessed 11 Sept. 2016.

Kolodny, Annette. “Dancing through the Minefield: Some Observations on the Theory, Practice, and Politics of Feminist Literary Criticism.” Feminist Criticism vol. 6 no. 1, 1980, pp. 1-25. JStor. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.odu.edu/stable/3177648. Accessed 9 Sept. 2016.

Lakoff, Robin Tolmach. “Language and Woman’s Place.” Language and Women’s Place: Text and Commentaries, ed. Mary Bucholtz. Oxford UP, 2004, pp. 39-75.

Lorde, Audrey. “Poems Are Not Luxuries.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 282-85.

Plain, Gill and Susan Sellers, editors. Introduction. A History of Feminist Literary Criticism. Cambridge UP, 2007, pp. 1-3.

Rawlings, John. “Jacques Derrida.” Stanford Presidential Lectures in the Humanities and Arts. Stanford U, 1999. Accessed 3 Nov. 2016. https://prelectur.stanford.edu/lecturers/derrida/.

Reed, Alison. Personal Interview. 13 Oct. 2016.

Rich, Adrienne. “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-vision.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 345-61.

Wolosky, Shira. Feminist Theory across Disciplines: Feminist Community and American Women’s Poetry. Adobe Digital Editions. NY: Routledge, 2013.

Wolosky, Shira. “Modest Muses: Feminist Literary Criticism.” Feminist Theory Across Disciplines: Feminist Community and American Women’s Poetry. New York; Taylor & Francis; Routledge, 2013, pp 1-22. Adobe Digital Editions. Accessed 26 Sept. 2016.