RAPIDLY CHANGING PARADIGMS

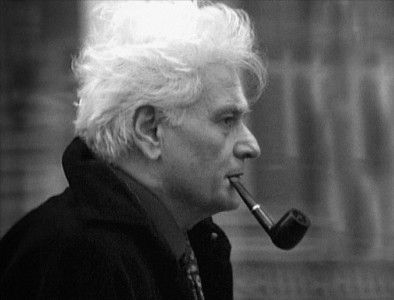

One of the difficulties of simply defining one or two theories for my focus is that Feminist Literary Theory is a combination of a wide variety of theoretical lenses, including Gender Theory, Reader-Response Theory, Close Reading, and Deconstruction among others, and the feminist approach to literature is currently in a state of change. In 1985, Susan S. Lanser notes that “[f]eminist criticism ha[d] been challenged and enriched in turn by new theories and practices whose possibilities it helped to create” (4). These were common methodologies at the start of the twenty-first century, but this is changing. Keeping in mind the changing nature of the field, I would consider women’s poetry and how women poets define themselves and other women through their poetry, through close-reading, linguistics, and likely, the theoretical position of philosophers like Derrida or Barthes.

Dr. Alison Reed, Old Dominion University

DIVERSITY AND PROMISE

The field of Feminist Literary Criticism seems a field of diverse theories and methodologies that has exploded in myriad directions. Feminist Literary scholars are pulling from all criticisms and drawing on many methodologies. The original feminist theorists have genuine staying power, and their theories are being fused with new theoretical and methodological approaches This makes the prevailing theories in Feminist Literary Criticism elusive. Trying to pin down particular favored theory is like trying to catch a greased pig—I think I’ve gotten it, but as soon as I think I do, it’s taken off again. In my interview with Dr. Alison Reed from ODU’s English Department, she mentioned that her current project focused on a performative social justice study, which is not based on a traditional text and is far from the traditional research paradigms of the twentieth-century.

THE THEORISTS (SOME OF THEM)

Early Feminist Theory that relied on Freud and Lacan, Byam points out, is based on psychoanalytic approaches that are inherently misogynistic, implying that women desire to be men. Even the feminist’s initial dichotomy of gender becomes problematic (102). While discussing feminist approaches to earlier eras, Byam states that feminist criticism has never been formalist, “if formalism means being preoccupied or even more than superficially interested in technique” (108). The critical conversations about methodology and theory drop off at the end of the twentieth-century, and then, the focus becomes applying various theories to different literary works. As for method, the tried and true research, collecting and examining secondary sources and Close Reading of the material, is still widely practiced, but even that seems to be giving way to experiment as scholars explore philosophical theories like Derrida‘s Deconstruction, and his assertion, “Everything is a text” (Rawlings).

WHO’S WHO? AND MIXING THINGS UP

The authoritative works, the works that appear significantly in present critical theory, go back to the original feminist theorists: Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, Kate Millet, Elaine Showalter, and Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar and to gender theorist Judith Butler figure heavily in contemporary scholarly criticism.

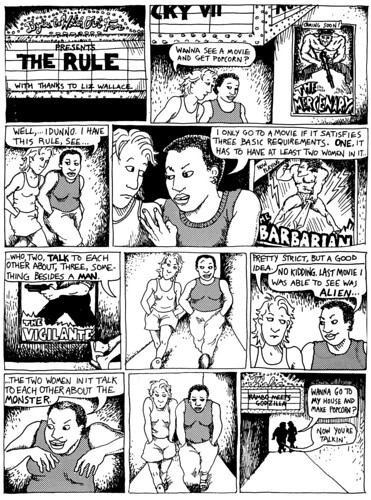

Moving into Reader-Response, retaining Close Reading, experimenting and applying many theories alone and in combination to literature old and new, and often that which the scholar deems significant enough for inclusion in the canon. Even Shira Wolosky considers women’s poetry through a variety of theoretical frameworks: including but not limited to feminist psychological, feminist political, and feminist poetics and aesthetic theories.

INTERSECTIONALITY TO POLITICAL ECOLOGY

Lanser points out the narrowly defined woman of early feminism, “only a small group of women whose politics may be no less conservative than those of the men with whom they sit on corporate and collegiate boards of trustees” and quotes Audre Lorde in pointing out that the women omitted from consideration were those who worked as domestics for these feminists “while [the feminists] were attending conferences on feminist theory” (5). The same trap that lead scholars to “the Utopian expectation that all works by women would be ideological correct in all particulars,” but were then faced with the dilemmas of classist and lesbian authors (Byam 114). Feminism has shifted its focus from white middle-class women to Intersectionality (recognizing the many ways women can be and are marginalized) and now toward political ecology, recognizing the real needs of marginalized women in other, particularly third-world, countries (Sunila Abeyskera 7). Scholars need to define themselves in terms of how their “own lived experiences reflect [their] literary commitments and affinities” and consider what other feminisms “look like” (Reed). Ihab Hassan quotes Steven Best and Douglas Kellner’s The Postmodern Turn, “Yet we must all heed politics because it structures our theoretical consents, literary evasions, critical rescuancies” (125). In these ways, scholars, including me, can avoid the unfortunate “you can’t speak for me”—“what about us” dichotomy and the vulnerabilities of early feminism and gynocritics that excluded and erased large populations of marginalized women.

Works Cited

Abeysekera, Sunila. “Shifting Feminisms: From Intersectionality to Political Ecology.” Talking Points. No. 2, 2007, pp. 6-11. Accessed 1 Nov. 2016. http://www.isiswomen.org/downloads/wia/wia-2007-2/02wia07_01TPoints-Sunila.pdf.

Hassan, Ihab. “Confessions of a Reluctant Critic: or, The Resistance to Literature.” The Emperor Redressed: Critiquing Critical Theory, edited by Dwight Eddins. Adobe Digital Editions. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 1995, pp. 118-31.

Lanser, Susan S. “Feminist Literary Criticism: How Feminist? How Literary? How Critical? NWSA Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1, Winter 1991, pp. 3-19. Jstor. Accessed 3 Nov 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4316102.

Rawlings, John. “Jacques Derrida.” Stanford Presidential Lectures in the Humanities and Arts. Stanford U, 1999. Accessed 3 Nov. 2016. https://prelectur.stanford.edu/lecturers/derrida/.

Reed, Alison. Personal Interview. 13 Oct. 2016.

Wolosky, Shira. Feminist Theory across Disciplines: Feminist Community and American Women’s Poetry. Adobe Digital Editions. NY: Routledge, 2013.