INTRODUCTION

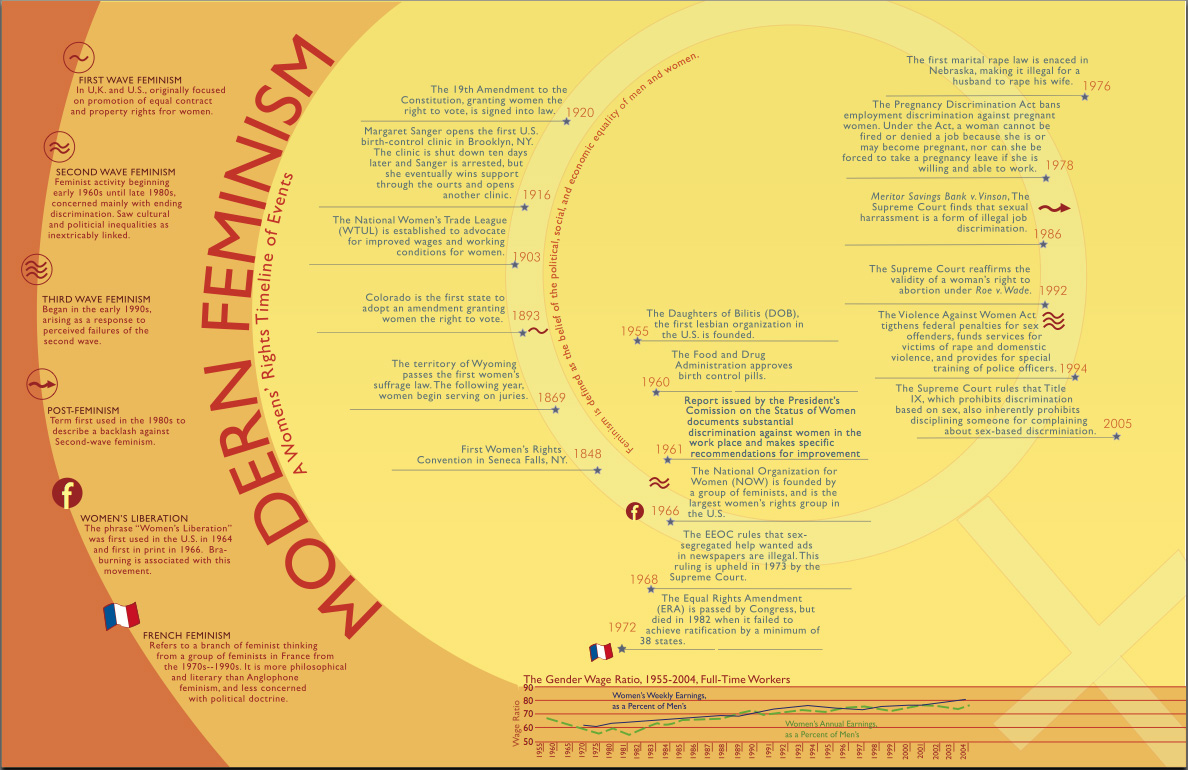

Before the proliferation women’s studies scholarship, women wrote all manner of things. Although the literary canon is still fraught with omissions, as an undergraduate I read many early women writers: women who wrote novels, poems, narratives, essays, books on manners, diaries, letters, and more. Still, for many, the genesis of feminist writing is Virginia Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own” (1928) where Woolf examines the dearth of scholarly spaces available to women. Some look closer to the present at Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949) in which she claimed, “One is not born, but rather, becomes a woman,” asserting man is first and women is second, and establishing woman as “Other” (Knellwolf 196). Woman as “other” forms the basis for much, if not all, feminist critical theory.

FEMINIST LITERARY CRITICISM

I see the real emergence of feminist literary criticism during the second-wave feminism, even as Gill Plain and Susan Sellers point out, feminist literary criticism wasn’t birthed in whole at this moment. Plain and Sellers say feminist literary criticism was the “culmination of centuries of women’s writing,” and of men “writing about women’s minds, bodies, art, and ideas” (2). It is during the later 1960s and 1970s that feminist writers began to build a formidable repertoire of feminist work. The activism of the feminist movement during this period motivated many women to counter the male dominated landscape, and they did this en masse. In creating this work, women created spaces for themselves in academia: in the 1960s, women’s studies classes appear; in the 1970s, we see the creation of women’s studies programs, and now, universities have entire women’s studies departments.

FEMINIST SCHOLARS & WOMEN’S STUDIES

The first women’s studies program was established at San Diego State University in 1970 (Ginsberg 10). Women’s studies programs at other universities were not far behind. “A feminist conference held at Cornell in January 1969” was the inspiration for their “Female Studies” program, later Cornell Women’s Studies (Cornell Chronicle), and now, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. Even with women’s studies programs established, the first feminist scholars came from all over and from a variety of different disciplines (Knellwolf 197). A quick survey of the mentions and sources which appear in just the few texts I’ve consulted reveal a diverse group of feminist writers who published feminist works during the 1970s, feminist writers like Elaine Showalter, Adrienne Rich, Kate Millett, Judith Fetterly, Germaine Greer, Sandra Gilbert, and Susan Gubar.

WHY WE NEED FEMINIST LITERARY CRITICISM

The exigency for the emergence of feminist literary criticism was that feminists found that women’s writing was omitted from the canon and that women who appeared in the literature were written from a male-centric point of view. According to Alice E. Ginsberg, “Women’s Studies had a very clear purpose, and that was to transform the university so that knowledge about women was no longer invisible, marginalized, or made ‘other’” (10). This omission, or erasure, of women from the history of literature, according to Annette Kolodny, quoting Clifford Gertz, “came to be ‘viewed collectively as a structural inconsistency’ within the very disciplines we studied” (1). My undergraduate experience of early British literature was comprised almost entirely of men; the exception was Jane Austen. The point of feminist literary criticism was to change things by seeking “to uncover its own origins” and “establish traditions of women’s writing and early ‘feminist’ thought” (Plain and Sellers 2). Feminist critical scholars set out to find their missing heritage, to amend the male-centric history to include women, and to show the value of the women they found. Feminist literary scholars also interrogate works to discover how a culture sees itself, and for me, I’m interested in exploring the ways that women writers define themselves and each other in the twenty-first century. I want to see how far women have moved past the male-centered definitions that have been applied to us for so long.

FEMINIST LITERARY CRITICISM & THE UNIVERSITY

The relationship between feminist literary criticism and the university as a whole was mirrored in the struggles of the feminist movement: “the definition of literary value privileged male writers’ engagement with warfare or politics over the more domestically centered literary works by female authors” (Knellwolf 199) just as the male endeavors were privileged over female endeavors. The feminist literary critic’s work is multidisciplinary, encompassing “a revisionist engagement with history and literary history, a revision of aesthetic standards and a radical critique of the representation of gender and gender roles as a part of a larger critique of cultural self-definition” (197). In the early years of feminist writing, many women “worked at the margins of the conventionally defined disciplines” as feminists were making inroads in established university programs. While, larger universities excluded women’s studies, lesser institutions created “space for courses specifically designed for women’s needs” (197).

CONCLUSION

From its early beginnings, women’s studies and feminism literary criticism have opened up new areas of scholarship. Second-wave feminism, criticized for focusing on the plight of middle class white women (Knellwolf 202), has entered a new phase and now recognizes minority women are multiply oppressed and multiply omitted. Additionally, feminist literary critics are abandoning binary ideas of gender and interrogating the role of gender and gender identification as it applies to literature. Feminist literary critics still seek to fill in the history of women’s writing.

More information: The Feminist Approach in Literary Criticism

WORKS CITED

9721-virginia-woolf.jpg. “Virginia Woolf Quotes.” QuoteAddict. http://quoteaddicts.com/topic/virginia-woolf-quotes/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2016.

Estroga, Ignatius Joseph. The Feminist Approach in Literary Criticism. 8 Jul. 2013. http://www.slideshare.net/josephestroga/the-feministapproachinliterarycriticism. Accessed 22 Sept. 2016. Slideshow.

Ginsberg, Alice E. The Evolution of American Women’s Studies Reflections on Triumphs, Controversies, and Change. New York: Palgrave-McMillan, 2008.

Ju, Anna. “Women’s Studies at Cornell Evolves over 40-year History to Include Sexual Minorities.” Cornell Chronicle, 4 Nov. 2009, http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/2009/11/cornell-looks-back-40-years-womens-studies. Accessed 21 Sept. 2016.

Knellwolf, Christa. “The History of Feminist Criticism.” Twentieth-Century Historical, Philosophical and Psychological Perspectivesedited by Christa Knellwolf and Christopher Norris. The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism Vol. 9. Cambridge UP, 2007, pp. 193-205. Cambridge Histories Online. https://www-cambridge-org.proxy.lib.odu.edu/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/D5A1D2AF4184FBC9438F19EF62A01E09/9781139055376c15_p191-206_CBO.pdf/the-history-of-feminist-criticism.pdf. Accessed 11 Sept. 2016.

Kolodny, Annette. “Dancing through the Minefield: Some Observations on the Theory, Practice, and Politics of Feminist Literary Criticism.” Feminist Criticism vol. 6 no. 1, 1980, pp. 1-25. JStor. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.odu.edu/stable/3177648. Accessed 9 Sept. 2016.

Plain, Gill and Susan Sellers, editors. Introduction. A History of Feminist Literary Criticism. Cambridge UP, 2007, pp. 1-3.