The Major Questions

According to Shira Wolosky, the major questions within feminist literary criticism are:

“what place have women had in what has been a resolutely male tradition of literature? How have women been represented, and how does this affect their own self-representation? What have been the (male) models of authorships, and how do these serve—or not—as models for the authorship of women? Are there gendered aspects of literary genres, of imagery, of language itself? What do we even mean by a ‘women’s’ literature? What would distinguish it from ‘men’s’ literature, other than the fact that women have written it?” (1)

Although the question of women’s absence in the canon does not appear in her list, Wolosky cites it as a “core concern” (1), which is a primary concern for me as are the final two questions.

The Origins of the Questions

Women had been excluded; therefore, women have struggled to have their writing canonized in a canon that “derive[d] from typically male experiences” (Code qtd. in Lang 313). British women like the Brontë sisters, Jane Austen, and George Eliot, among others, had found their ways into the male canon (Grace 12) earlier than American women. By the time I was studying English in 2000, women figured prominently in literature.

The Ongoing Research

In researching feminist literary criticism as a subject, most of the writing occurred in the late seventies and throughout the eighties, trickling into the nineties, and when the conversation turns in favor of feminist criticisms of specific literary works. While researching, I found “newer” texts were frequently reprints of older work.

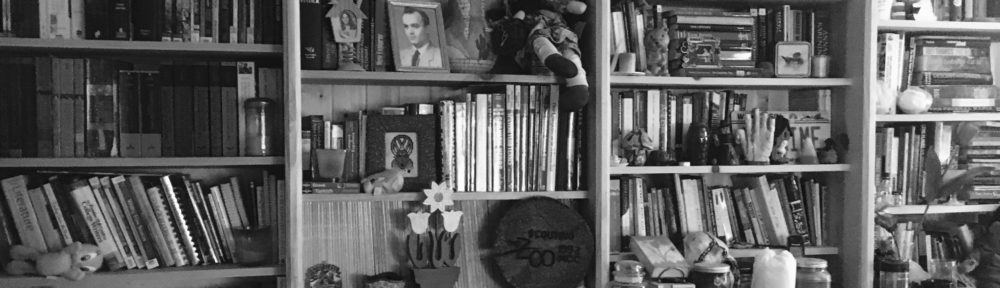

My own bookcase features a wealth of feminist writing and criticism from the eighties and nineties and includes authors such as Antonia Fraser, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, Elaine Showalter, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, as well as gender studies author, Judith Butler. These women illustrate an energetic conversation about how women have been viewed, ignored, exploited, benefitted, and eventually, recognized as people and authors. Through examining recent scholarship, the focus is shifting from the inclusion of women’s writing to criticism focused on individual works.

Presently, new paradigms to assess how women are portrayed in film, and in literature include approaches like Shira Wolosky’s, examining literature in terms of gender and cultural theories through a decidedly feminist lens, and Wolosky, and Cheryl Glenn’s, examining women’s silences and modesties as deliberate and political. And, Daphne M. Grace explores the female body in literature, “locating and discussing the relationship of the gendered body and consciousness” in writing by men and women (15).

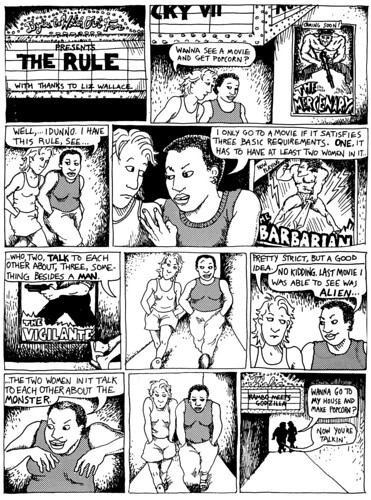

Scott Selisker presents “The Bechdel Test,”[i] based on one of Alison Bechdel’s comic strip episodes in Dykes to Watch Out For, which was dubbed “vernacular criticism” by Brian Droitcour (Selisker 505), examines how women are portrayed in films, in which a film must pass three criteria (514). Based on Selisker’s paraphrasing of Heather Love on network studies: “this empirical style of reading can and should be applied to the networks within literary texts, too” (508), and we should consider women in literature likewise. Selisker also suggests Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus’s approach, examining texts in terms of “surface reading,” or “describing the ‘patterns that exist writing and across texts’” (508), showing how women act as network lines for the benefit of men within texts.

Where Does This Lead?

My focus, as I envision it, interrogates women’s poetry to see how women present themselves and other women within the poetry they write, which may incorporate any of these new approaches. Of course, “the way we view our bodies is synonymous with how we view ourselves” (Bleier qtd. in Grace 12), so with Judith Butler’s lead, considering gender as a construct and a performance and how women construct themselves female, the differences between women’s early writing and their mature writing should reveal whether their construction or (re)construction of gender over time reinforces or dismantles their earlier perceptions of their respective gender identities.

[i] Other “vernacular criticisms” include “The Mako Mori Test,” “The Sexy Lamp Test,” and “The Furiosa Test”

Works Cited

Grace, Daphne. “Cognition, Consciousness, and Literary Texts.” Beyond Bodies: Gender, Literature, and the Enigma of Consciousness. New York; Rodopi, 2014, pp 9-32. Adobe Digital Editions. Accessed 26 Sept. 2016.

Lang, James C. “Feminist Epistemologies of Situated Knowledges: Implications for Rhetorical Argumentation.” Informal Logic, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2010, pp. 309-334. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwiV4eeWnsbPAhXGNz4KHcCVBvwQFggkMAE&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwindsor.scholarsportal.info%2Fojs%2Fleddy%2Findex.php%2Finformal_logic%2Farticle%2Fdownload%2F3036%2F2424&usg=AFQjCNECZegOhT707ziw1dvgImlFwgbBFA&sig2=5i0UOsz3eTZtivlHFEVS7Q

Selisker, Scott. “The Bechdel Test and the Social Form of Character Networks.” New Literary History, Vol. 46, No. 3, Summer 2015, pp. 505-523. Project Muse. DOI: 10.1353/nlh.2015.0024.

Wolosky, Shira. “Modest Muses: Feminist Literary Criticism.” Feminist Theory Across Disciplines: Feminist Community and American Women’s Poetry. New York; Taylor & Francis; Routledge, 2013, pp 1-22. Adobe Digital Editions. Accessed 26 Sept. 2016.