Theoretical & Epistemological Alignment

Sinéad Travers @travers_sinead on Twitter

My background is in creative writing, poetic, and feminist theories. Other approaches useful in interrogating texts include feminist, gender, creative writing, poetic, literary, rhetoric, cultural, Marxist, and linguistic theories. Yes, there are a lot, but why limit myself in terms of how I approach my subject. No, I haven’t listed all the theories, but I see myself using many and in combinations. My experience has been that the primary theories used are determined by the immediate task at hand. Since I want to explore how women define themselves and other women as women in poetry, questions of self-identification, language usage, creative expression, cultural positioning, and power and class structures all seem to be fruitful avenues of exploration. As T. S. Eliot says, “we might remind ourselves that criticism is an inevitable as breathing” (111).

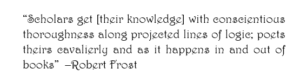

My experience with the ways other scholars have approached literary criticism and my creative writing background have allowed me to approach literature under the lens of creative writing theory, which allows a critical approach based on the writer’s act of constructing the work to elicit specific responses from readers as well as the reader’s actual response, in Frost’s words, “No tears for the writer, no tears for the reader” (11), or Tess Gallagher, “the reader is also the maker of the poem as it lives again in his consciousness” (107).

Although I won’t eschew traditional theoretical paradigms, I intend for my professional alignment to be new, to deviate from what others have done, but not too far afield. As I remain open-minded, see what the theorists have told us, I can create new approaches. I had done so in my master’s degree work with much satisfaction and success. For example, I compared Heart of Darkness to Jane Eyre using a female gothic lens to interrogate both works, and later, applying the theoretical framework established in Martin Bidney’s “Fire, Flutter, Fall, and Scatter: A Structure in the Epiphanies of Hawthorne’s Tales,” I examined works by Raymond Carver to establish patterns surrounding epiphanic moments, which revealed epiphanies not solidly established in previous research. Bidney had applied the theoretical framework of images from Serge Lemaire and Norman Holland to Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” (59).

Objects of Study

Audre Lorde

My primary objects of study for my dissertation will be poems written by women to see how women are defined within that poetry because “[p]oetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought” (Lorde 283). I’m still open to new positioning and possibilities. With these, I envision my specific theoretical approaches in terms of how these approaches address and figure women in context as well as how, given the nature of creative writing/poetic theory, women use the tools provided in self-identification. Elements of creative writing theory such as meter, voice, line breaks, and musicality inform creative writing and provide new ways of seeing such as line breaks, which “can record the slight (but meaningful) hesitations between word and word that are characteristic of the mind’s dance among perceptions but which are not noted by grammatical punctuation” (Levertov 266).

In poetic criticism, much of the research has involved individual poems, books of poetry, or individual poets, and these poems, books, and poets are most often already canonized. My intent is to break from this canonized work and explore the work of women who are writing now, are new to the field, having written few books, and have published their work within the last decade.

Agenda

-Sapere Aude

Although things have changed since 1977 when Alicia Ostriker noted, “What has not changed is that most critics and professors of literature, including modern literature, deny that ‘women’s poetry,’ as distinct from poetry by individual women, exists. Many women writers agree. Some will not permit their work to appear in women’s anthologies” (311), women still struggle to find recognition of their work; furthermore, her comment on the work that was “explicitly female in the sense that the writer has consciously chosen not to “write like a man” but to explore experiences central to her sex” may still be true to an extent (310).

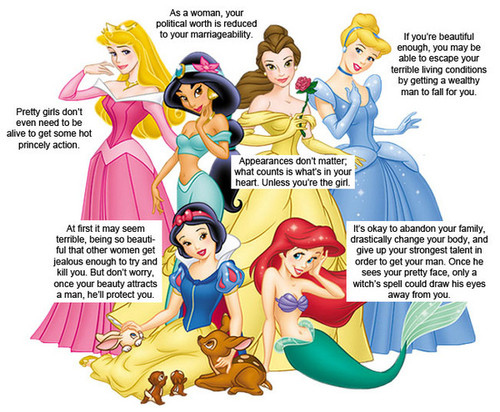

Lakoff’s consideration of women and language from the 1970s still provides the “overall effect of ‘women’s language’…is this: it submerges a woman’s personal identity” (42), and as she continues discussing the differences in production and cultural expectation, she says, “women are allowed to fuss and complain, but only a man can bellow in rage” (45). Adrienne Rich comments on the poetic climate of the 1970s when she discusses the “thwarting of [a woman’s] needs by a culture controlled by males” and problems this creates “for the woman writer” (349). This oppression and inequality for women still exists. Men are still more recognized and more compensated for their poetic work, but she says, women are writing poetry, studying literature, and “looking eagerly for guides, maps, possibilities; and over and over in the ‘words’ masculine persuasive force’ of literature she comes up against something that negates everything she is about; she meets the image of Woman in books written by men” (351).

Women still don’t have equal rights. And though women have made progress in some areas, women still struggle with issue of body autonomy. Rape is rarely punished, and now we have presidential candidates who speak openly about sexually assaulting women with no repercussions. Safe access to abortion, which had been secured through Roe v Wade, is being rolled back, creating hardships for poor women in particular. For women, still, poetry provides Frost’s “momentary stay against confusion” (11).

Personal/Professional Objectives

favim.com

The broader lens, under which this women’s poetry falls, is American literature, I will continue my inquiry, collecting and comparing both poetry and fiction, because “No poet, no artist of any art, has is complete meaning alone….you must set him, for contrast and comparison among the dead” (Eliot 112). I plan to focus most heavily in the 20th and 21st centuries, in order to comparative work, I will need to expand out. In poetry and prose, “the passion for the things of the world and the passion for naming them must be in him indistinguishable” (Levertov 263), and to further Levertov’s point, the passion for investigating this process of naming is why I’ve chosen to research in this way.

Works Cited

Bidney, M. “Fire, Flutter, Fall, and Scatter: A Structure in the Epiphanies of Hawthorne’s Tales.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 50 no. 1, 2008, pp. 58-89. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/tsl.2008.0000. Accessed 19 Oct. 2016.

Eliot, T. S. “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Twentieth-Century American Poetics: Poets on the Art of Poetry, ed. Dana Gioia, David Mason, and Meg Schoerke. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2004, pp. 111-16.

Frost, Robert. “The Figure a Poem Makes.” Twentieth-Century American Poetics: Poets on the Art of Poetry, ed. Dana Gioia, David Mason, and Meg Schoerke. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2004, pp. 11-12.

Gallagher, Tess. “The Poem as a Time Machine.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 104-116.

Lakoff, Robin Tolmach. “Language and Woman’s Place.” Language and Women’s Place: Text and Commentaries, ed. Mary Bucholtz. Oxford UP, 2004, pp. 39-75.

Levertov, Denise. “On the Function of the Line.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 265-72.

—. “Origins of a Poem.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 254-64.

Lorde, Audrey. “Poems Are Not Luxuries.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 282-5.

Ostriker, Alicia. “The Nerves of a Midwife: Contemporary American Women’s Poetry.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 309-27.

Rich, Adrienne. “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-vision.” Claims for Poetry, ed. Donald Hall. U of Michigan P, 2007, pp. 345-61.

How interesting! I have not performed a lot of analysis of poetry, through the lenses you mention or others. That said, I find you present a subtle but compelling metaphor between the control of women’s bodies of work and their physical bodies, and that the value of women’s poetry and persons are on a similar trajectory–that in order to be valued, women must be the sole owners of their passions in both arenas. The challenge, as you say, is not in the desire of women to be in control, but that we are still struggling with bodily autonomy, both in print and in person. I will be very interested to see how your analysis plays out in your writing going ahead!