Lakoff, Robin Tolmach. “Language and Woman’s Place.” Language and Women’s Place: Text and Commentaries, ed. Mary Bucholtz. Oxford UP, 2004, pp. 39-75.

I first read Lakoff under the impression that the piece was written in 2004, but upon reading her description of the word “groovy,” further investigation revealed that it was, in fact, originally written in 1973. Later, she mentions President Nixon and other famous figures from the 1970s. Lakoff’s “Language and Women’s Place” from Stanford.edu.

The struggle with her older scholarship is that Lakoff makes statements, which were likely innocuous in 1973, that today seem somewhat misguided in light of forward progress for women. However, Lakoff’s discussion of women’s language in terms of linguistics still reveals information that is true today, and she points directly to parts of speech in which the content has changed since the 1970s but these locations still may contain artifacts of the original syntactical patterns she discusses.

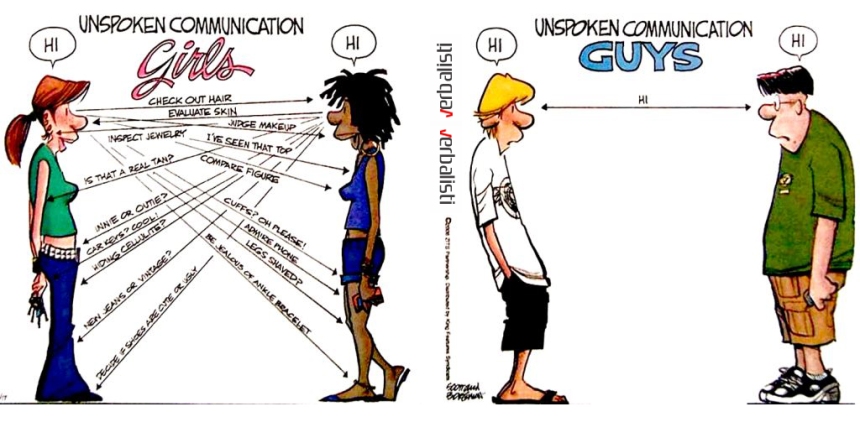

Her primary argument is that women use language differently than men do, that women tend to equivocate and men tend to be more assertive, and societal expectations reinforce this dichotomy. The linguistic approach to the evaluation of language holds much promise in my field as New Criticism seems to be falling out of favor, linguistic approaches would approximate New Criticism’s theoretical approach and should provide similar results.

Lakoff says, “we can use our linguistic behavior as a diagnostic of our hidden feelings about things” (39), and my interest in a poet’s hidden feelings about women. Lakoff’s discussion about the differences between the adjectives that men and women use is insightful. She provides a few examples of specificity when considering women’s adjectives as opposed to men’s more general descriptions.

See “Linguistics shows that being a single guy has gotten better and being a single woman has gotten worse” by Kate Bolick

Lakoff’s position is “women experience linguistic discrimination in two ways”: how women learn to speak and in the subtleties of language that describe them (39). In her discussion of the use of “lady” and “girl” she makes an excellent point about tagging professions with “women” when there is no equivalent “man” tag, for example, “woman doctor” (54).

When considering a linguistic theoretical approach and using Lakoff’s observations, examining how frequently women use “utterances” and the purposes and conditions of those utterances in poetry may yield fruitful information about differences in first, how women differ from men in their speech, and second, how women are defined differently from men (or perhaps more specifically, how the feminine is distinct from masculine).

Lakoff also considers the ways in which women are represented in language. The connotations of words used in connection with women show that some words have “a special meaning that, by implication rather than outright assertion, is derogatory to women as a group” (51). She says the use of euphemisms for women, in particular, the use of “lady,” and she discusses “girl” in the same context, are used to establish or reinforce a code which expects women to be “non-sexual” (55). She points to the word “woman” as being overtly sexual, and often terms applied innocuously to men, are overtly sexual when applied to women (54).